bio.wikisort.org - Animal

At least six monkey species are native to Panama. A seventh species, the Coiba Island howler (Alouatta coibensis) is often recognized, but some authors treat it as a subspecies of the mantled howler, (A. palliata).[1] An eighth species, the black-headed spider monkey is also often recognized, but some authorities regard it as a subspecies of Geoffroy's spider monkey.[2] All Panamanian monkey species are classified taxonomically as New World monkeys, and they belong to four families. The Coiba Island howler, mantled howler, black-headed spider monkey and Geoffroy's spider monkey all belong to the family Atelidae. The white-faced capuchins and Central American squirrel monkey belong to the family Cebidae. the family that includes the capuchin monkeys and squirrel monkeys. The Panamanian night monkey belongs to the family Aotidae, and Geoffroy's tamarin belongs to the family Callitrichidae.

The mantled howler, the Panamanian night monkey, Geoffroy's spider monkey and the Panamanian white-faced capuchin all have extensive ranges within Panama.[3][4][5][6][7] Geoffroy's tamarin also has a fairly wide range within Panama, from west of the Panama Canal to the Colombian border.[8] The range of the black-headed spider monkey and Colombian white-faced capuchin within Panama are limited to the eastern portion of the country near the Colombian border.[9][7] The Central American squirrel monkey only occurs within Panama in the extreme western portion of the country, near Costa Rica.[10] It now has a smaller range within Panama than in the past, and is no longer found in its type locality, the city of David.[10] As its name suggests, the Coiba Island howler is restricted to Coiba Island.[11] The Azuero howler monkey (Alouatta coibensis trabeata or Alouatta palliata trabeata), which is considered a subspecies of either the Coiba Island howler or the mantled howler, is restricted to the Azuero Peninsula.[3]

The black-headed spider monkey is the largest Panamanian monkey with an average size of 8.89 kilograms (19.6 lb) for males and 8.8 kilograms (19 lb) for males.[12][13] Geoffroy's spider monkey is the next largest, followed by the howler monkey species. Geoffroy's tamarin is the smallest Panamanian monkey, with an average size of about 0.5 kilograms (1.1 lb).[14]

One Panamanian monkey, the black-headed spider monkey, is considered to be critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Geoffroy's spider monkey is considered to be endangered.[3][9] The Central American squirrel monkey was once considered endangered, but its conservation status was upgraded to vulnerable in 2008.[10] The Coiba Island howler is also considered to be vulnerable.[11] Three species, the mantled howler, the white-faeced capuchin and Geoffroy's tamarin are rated as "least concern" from a conservation standpoint.[5][6][8]

Key

| Latin Name | Latin binomial name, or scientific name, of the species |

| Common Name | Common name of the species, per Wilson, et al. Mammal Species of the World (2005) |

| Family | Family within New World monkeys to which the species belongs |

| Average Size – Male | Average size of adult male members of the species, in kilograms and pounds |

| Average Size – Female | Average size of adult female members of the species, in kilograms and pounds |

| Conservation Status | Conservation status of the species, per IUCN as of 2008 |

Panamanian monkey species

| Latin Name | Common Name | Family | Average Size – Male | Average Size – Female | Conservation Status | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alouatta coibensis[a] | Coiba Island howler | Atelidae | 7.150 kg (15.76 lb) | 5.350 kg (11.79 lb) | Vulnerable | [11][12][15] |

| Alouatta palliata | Mantled howler | Atelidae | 7.150 kg (15.76 lb) | 5.350 kg (11.79 lb) | Least Concern | [5][12][16] |

| Aotus zonalis[b] | Panamanian night monkey | Aotidae | 0.889 kg (1.96 lb) | 0.916 kg (2.02 lb) | Data Deficient | [4][17][18] |

| Ateles fusciceps[c] | Black-headed spider monkey | Atelidae | 8.890 kg (19.60 lb) | 8.800 kg (19.40 lb) | Critically Endangered | [9][13][19] |

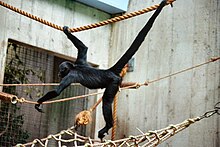

| Ateles geoffroyi | Geoffroy's spider monkey | Atelidae | 8.210 kg (18.10 lb) | 7.700 kg (16.98 lb) | Endangered | [3][12][20] |

| Cebus capucinus[d] | Colombian white-faced capuchin | Cebidae | 3.668 kg (8.09 lb) | 2.666 kg (5.88 lb) | Least Concern | [7][6][21][22] |

| Cebus imitator | Panamanian white-faced capuchin | Cebidae | 3.668 kg (8.09 lb) | 2.666 kg (5.88 lb) | Least Concern | [7][6][21][22] |

| Saguinus geoffroyi | Geoffroy's tamarin | Callitrichidae | 0.486 kg (1.07 lb) | 0.507 kg (1.12 lb) | Least Concern | [8][14][23] |

| Saimiri oerstedii | Central American squirrel monkey | Cebidae | 0.829 kg (1.83 lb) | 0.695 kg (1.53 lb) | Vulnerable | [10][22][24] |

Footnotes

- a Sometimes regarded as a subspecies of Alouatta palliata.[11] Sizes given are for Alouatta palliata.

- b Sometimes regarded as a subspecies of Aotus lemurinus, in which case its trinomial name is Aotus lemurinis zonalis.[17]

- c Sometimes regarded as a subspecies of Ateles geoffroyi.[2]

- d Formerly reagrded to be conspecific with Cebus imitator. Sizes given are for Cebus imitator.[7]

References

- Rylands, A.; Groves, C.; Mittermeier, R.; Cortes-Ortiz, L. & Hines, J. (2006). "Taxonomy and Distributions of Mesoamerican Primates". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.; Pavelka, M. & Luecke, L (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. Springer. pp. 29–80. ISBN 0-387-25854-X.

- Collins, A. (2008). "The taxonomic status of spider monkeys in the twenty-first century". In Campbell, C. (ed.). Spider Monkeys. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–67. ISBN 978-0-521-86750-4.

- Cortes-Ortíz, L.; Solano-Rojas, D.; Rosales-Meda, M.; Williams-Guillén, K.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Marsh, L.K.; Canales-Espinosa, D.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2021). "Ateles geoffroyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T2279A191688782. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T2279A191688782.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Link, A. (2021). "Aotus zonalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39953A17922442. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39953A17922442.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Cortes-Ortíz, L.; Rosales-Meda, M.; Williams-Guillén, K.; Solano-Rojas, D.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; de la Torre, S.; Moscoso, P.; Rodríguez, V.; Palacios, E.; Canales-Espinosa, D.; Link, A.; Guzman-Caro, D.; Cornejo, F.M. (2021). "Alouatta palliata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39960A190425583. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39960A190425583.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- de la Torre, S.; Moscoso, P.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Rosales-Meda, M.; Palacios, E.; Link, A.; Lynch Alfaro, J.W.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2021). "Cebus capucinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T81257277A191708164. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T81257277A191708164.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Mittermeier, Russell A. & Rylands, Anthony B. (2013). Mittermeier, Russell A.; Rylands, Anthony B.; Wilson, Don E. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume 3, Primates. Lynx. pp. 412–413. ISBN 978-8496553897.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Link, A.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Palacios, E.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2021). "Saguinus geoffroyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T41522A192551955. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T41522A192551955.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Moscoso, P.; Link, A.; Defler, T.R.; de la Torre, S.; Cortes-Ortíz, L.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Shanee, S. (2021). "Ateles fusciceps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T135446A191687087. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T135446A191687087.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Solano-Rojas, D. (2021). "Saimiri oerstedii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T19836A17940807. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T19836A17940807.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; Cuarón, A.D.; Shedden, A.; Rodriguez-Luna, E.; de Grammont, P.C.; Link, A. (2021). "Alouatta palliata ssp. coibensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T43899A195441006. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T43899A195441006.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Di Fiore, A. & Campbell, C. (2007). "The Atelines". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M. & Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. The Oxford University Press. pp. 155–177. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Mammals. Pogonias Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- Defler, T. (2004). Primates of Colombia. Conservation International. pp. 163–169. ISBN 1-881173-83-6.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Fernandez-Duque, E. (2007). "Aotinae". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M.; Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. The Oxford University Press. pp. 139–154. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Jack, K. (2007). "The Cebines". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M.; Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. The Oxford University Press. pp. 107–120. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии