bio.wikisort.org - Animal

The largest prehistoric animals include both vertebrate and invertebrate species. Many of them are described below, along with their typical range of size (for the general dates of extinction, see the link to each). Many species mentioned might not actually be the largest representative of their clade due to the incompleteness of the fossil record and many of the sizes given are merely estimates since no complete specimen have been found. Their body mass, especially, is largely conjecture because soft tissue was rarely fossilized. Generally the size of extinct species was subject to energetic[1] and biomechanical constraints.[2]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Non-mammalian synapsids (Synapsida)

Caseasaurs (Caseasauria)

The herbivorous Alierasaurus was the largest caseid and the largest amniote to have lived at the time, with an estimated length around 6–7 m (20–23 ft).[3] Cotylorhynchus hancocki is also large, with an estimated length and weight of at least 6 m (20 ft)[4] and more than 500 kg (1,100 lb).[5]

Edaphosaurids (Edaphosauridae)

The largest edaphosaurids were Lupeosaurus at 3 m (9.8 ft) long[6] and Edaphosaurus, which could reach even more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in length.[7]

Sphenacodontids (Sphenacodontidae)

The biggest carnivorous synapsid of Early Permian was Dimetrodon, which could reach 4.6 m (15 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb).[8] The largest members of the genus Dimetrodon were also the world's first fully terrestrial apex predators.[9]

Tappenosauridae

The Middle Permian Tappenosaurus was estimated at 5.5 m (18 ft) in length, nearly as large as the largest dinocephalians.[10]

Therapsids (Therapsida)

Anomodonts (Anomodontia)

The plant-eating dicynodont Lisowicia bojani is the largest-known of all non-mammalian synapsids, at 4.5 m (15 ft) long, 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in) tall and 9,000 kg (20,000 lb) in body mass.[11][12][13]

Dinocephalians (Dinocephalia)

Among the largest carnivorous non-mammalian synapsids was the dinocephalian Anteosaurus, which was 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long, and weighed 500–600 kg (1,100–1,300 lb).[14][15] Fully grown Titanophoneus from the same family Anteosauridae likely had a skull of 1 m (3.3 ft) long.[15] Another enormous dinocephalian was the Late Permian Eotitanosuchus (a possible synonym to Biarmosuchus[16]). Adult specimens could reach 6 m (20 ft) in length and over 600 kg (1,300 lb) in weight.[16]

Gorgonopsians (Gorgonopsia)

Inostrancevia latifrons is the largest known gorgonopsian, with a skull length of more than 60 cm (24 in), a total length approaching 3.5 m (11 ft) and a mass of 300 kg (660 lb).[17] Rubidgea atrox is the largest African gorgonopsian, with skull of nearly 45 cm (18 in) long.[18] Other large gorgonopsians include Dinogorgon with skull of ~40 cm (16 in) long,[19] Leontosaurus with skull of almost 40 cm (16 in) long,[18] and Sycosaurus with skull of ~38 cm (15 in) long.[18]

Therocephalians (Therocephalia)

The largest of therocephalians is Scymnosaurus,[20][21] which reached a size of the modern hyena.[22]

Non-mammalian cynodonts (Cynodontia)

- The largest known non-mammalian cynodont is Scalenodontoides, a traversodontid, which had a maximum skull length of approximately 617 millimetres (24.3 in) based on a fragmentary specimen.[23]

- Paceyodon davidi was the largest of morganucodontans, cynodonts close to mammals. It is known by a right lower molariform 3.3 mm (0.13 in) in length, which is bigger than molariforms of all other morganucodontans.[24]

- The largest known docodont was Castorocauda, almost 50 cm (20 in) in length.[25]

Mammals (Mammalia)

Non-therian mammals

Gobiconodonts (Gobiconodonta)

The largest gobiconodont and the largest well-known Mesozoic mammal was Repenomamus.[26][27][28][29][30][31] The known adult of Repenomamus giganticus reached a total length of around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and an estimated mass of 12–14 kg (26–31 lb).[28] With such parameters it surpassed in size several small theropod dinosaurs of the Early Cretaceous.[32] Gobiconodon was also a large mammal,[30][31] it weighed 5.4 kilograms (12 lb),[28] had a skull of 10 cm (3.9 in) in length, and had 35 cm (14 in) in presacral body length.[33]

Multituberculates (Multituberculata)

The largest multituberculate[34] Taeniolabis taoensis is the largest non-therian mammal known, at a weight possibly exceeding 100 kg (220 lb).[35]

Monotremes (Monotremata)

- The largest known monotreme (egg-laying mammal) ever was the extinct long-beaked echidna species known as Murrayglossus, known from a couple of bones found in Western Australia. It was the size of a sheep, weighing probably up to 30 kg (66 lb).[36]

- The largest known ornithorhynchid is Obdurodon tharalkooschild, it was even larger than 70 cm (28 in)-long Monotrematum sudamericanum.[37]

- Kollikodon was likely the largest monotreme in Mesozoic. Its body length could be up to a 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[38]

Metatherians (Metatheria)

- The largest non-marsupial metatherian was Thylacosmilus, weigh 80 to 120 kilograms (180 to 260 lb),[39][40] one estimate suggesting even 150 kg (330 lb).[41] Proborhyaenid Proborhyaena gigantea is estimated to weigh over 50 kg (110 lb) and possibly reached 150 kg (330 lb).[42] Australohyaena is another large metatherian, weighing up to 70 kilograms (150 lb).[43]

- Stagodontid mammal Didelphodon was one of the largest Mesozoic metatherians and all Cretaceous mammals.[44] Its skull could reached over 10 centimetres (3.9 in) in length[45] and a weight of complete animal was 5.2 kilograms (11 lb).[46]

Marsupials (Marsupialia)

- The largest known marsupial, and the largest metatherian, is the extinct Diprotodon, about 3 m (9.8 ft) long, standing 2 m (6 ft 7 in) tall and weighing up to 2,786 kg (6,142 lb).[47] Fellow vombatiform Palorchestes azael was similar in length being around 2.5 m (8.2 ft), with body mass estimates indicating it could exceed 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[48]

- The largest known carnivorous marsupial was Thylacoleo carnifex. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show they averaged 101 to 164 kg (223 to 362 lb) in weight.[49][50]

- The largest known kangaroo was an as yet unnamed species of Macropus, estimated to weigh 274 kg (604 lb),[51] larger than the largest known specimen of Procoptodon, which could grow up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) and weigh 230 kg (510 lb).[52] Some species from the genus Sthenurus were similar in size or a bit larger than the extant grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus).[53]

- The largest potoroid ever recorded was Borungaboodie, which was nearly 30% bigger than the largest living species and weighted up to 10 kg (22 lb).[54]

Non-placental eutherians

Cimolestans (Cimolesta)

The largest known cimolestan is Coryphodon, 1 m (3 ft 3 in) high at the shoulder, 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) long[55][56] and up to 700 kg (1,500 lb) of mass.[57] Barylambda was also a huge mammal, at 650 kg (1,430 lb).[58] Wortmania and Psittacotherium from the group Taeniodonta were among the largest mammals of the Early Paleocene.[59] Lived as soon as half a million years after K–Pg boundary, Wortmania reached 20 kg (44 lb) in body mass. Psittacotherium, which appeared two million years later, reached 50 kg (110 lb).[59]

Leptictids (Leptictida)

The largest leptictid ever discovered is Leptictidium tobieni from the Middle Eocene of Germany. It had a skull 101 mm (4.0 in) long, head with trunk 375 mm (14.8 in) long, and tail 500 mm (20 in) long.[60] Close European relatives from the same family Pseudorhyncocyonidae had skulls of 67–101 mm (2.6–4.0 in) in length.[60]

Even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla)

- The largest known land-dwelling artiodactyl was Hippopotamus gorgops with a length of 4.3 m (14 ft), a height of 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in), and a weight of 5 t (11,000 lb).[61]

- Daeodon and similar in size and morphology Paraentelodon[62] were the largest-known entelodonts that ever lived, at 3.7 m (12 ft) long and 1.77 m (5.8 ft) high at the shoulder.[63] The huge Andrewsarchus from the Eocene of Inner Mongolia had skull 83.4 cm (32.8 in) long[64] though the taxonomy of this genus is disputive.[65][66]

- The largest of Bovinae as well as the largest bovid was Bison latifrons. It reached a weight from 1,250 kg (2,760 lb)[67][68] to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb),[69] 4.75 m (15.6 ft) in length, shoulder height of 2.31 m (7.6 ft),[70] and had horns that spanned 2.13 m (7 ft 0 in).[71] The North American Bison antiquus reached up to 4.6 m (15 ft) long, 2.27 m (7.4 ft) tall, weight of 1,588 kg (3,501 lb),[72] and horn span of 1 m (3.3 ft).[70] The African Pelorovis reached 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight and had bony cores of the horns about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long.[73] Another enormous bovid, the african giant buffalo (Syncerus antiquus) reached 3 m (9.8 ft) in length from muzzle to the end of the tail, 1.85 m (6.1 ft) in height at the withers, 1.7 m (5.6 ft) in height at the hindquarters,[74][75] and the distance between the tips of its horns was as large as 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in).[74] Aside from local populations and subspecies of extant species, such as the gaur population in Sri Lanka, European bison in British Isles, Caucasian wisent and Carpathian wisent, the largest modern extinct bovid is aurochs (Bos primigenius) with an average height at the shoulders of 155–180 cm (61–71 in) in bulls and 135–155 cm (53–61 in) in cows, while aurochs populations in Hungary had bulls reaching 155–160 cm (61–63 in).[76] The kouprey (Bos sauveli), reaching 1.7–1.9 m (5 ft 7 in – 6 ft 3 in) in shoulder height,[77][78] has existed since the Middle Pleistocene[79] and is also considered to be possibly extinct.[80][81]

- The long-legged Megalotragus is possibly the largest known alcelaphine bovid,[82] bigger than the extant wildebeest.[83] The tips of horns of M. priscus were located at a distance of about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) from each other.[84]

- The extinct cervid Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) reached over 2.1 m (7 ft) in height, 680 kg (1,500 lb) in mass and could have antlers spanning up to 4.3 m (14 ft) across, about twice the maximum span for a moose's antlers.[85][86] The giant moose (Cervalces latifrons) reached 2.1 to 2.4 m (6.9 to 7.9 ft) high[87] and was twice as heavy as the Irish elk but its antler span at 2.5 m (8.2 ft) was smaller than that of Megaloceros.[88][89] North American stag-moose (Cervalces scotti) reached 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length and a weight of 708.5 kilograms (1,562 lb).[90][91]

- The largest known giraffid, aside from the extant giraffe, is Sivatherium, with a body weight of 1,250 kg (2,760 lb).[92]

- The largest protoceratid was Synthetoceras, it reached 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long and 150–200 kg (330–440 lb) in mass.[93][94]

- The largest known wild suid to ever exist was Kubanochoerus gigas, having measured up to 500 kg (1,100 lb) and stood around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall at the shoulder.[95] Megalochoerus could be similar in size, possibly weighing 303 kg (668 lb) or 526 kg (1,160 lb).[96]

- The largest camelid was Titanotylopus from the Miocene of North America. It possibly reached 2,485.6 kg (5,480 lb) and a shoulder height of over 3.4 m (11 ft).[97][98] The Syrian camel (Camelus moreli) was twice as big as the modern camels.[99] It was 3 m (9.8 ft) at the shoulder[100] and 4 m (13 ft) tall.[99] Camelops had legs to be 20% longer than that of Dromedary, and was about 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) tall at the shoulder and weighed about 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[101]

Cetaceans (Cetacea)

- The largest of known Eocene archeocete whales was Basilosaurus at 17–20 m (56–66 ft) in length.[102][103][104]

- The largest prehistoric sperm whale, or toothed whale was Livyatan melvillei weighing in at about 57 tonnes (63 short tons).[105][106]

- The largest squalodelphinid was Macrosqualodelphis at 3.5 m (11 ft) in length.[107]

- Some Neogene rorquals were comparable in size to modern huge relatives. Parabalaenoptera was estimated to be about the size of the modern gray whale,[108] about 16 m (52 ft) long. Some balaenopterids perhaps rivaled the blue whale in terms of size,[108] though other studies disagree that any baleen whale grew that large in the Miocene.[109]

Odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla)

- The largest known perissodactyl, and the second largest land mammal (see Palaeoloxodon namadicus) of all time was the hornless rhino Paraceratherium. The largest individual known was estimated at 4.8 m (15.7 ft) tall at the shoulders, 7.4 m (24.3 ft) in length from nose to rump, and 17 t (18.7 short tons) in weight.[110][111]

- Some prehistoric horned rhinos also grew to large sizes. The biggest Elasmotherium reached up to 5–5.2 m (16–17 ft) long,[112] 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) high[113] and weighed 3.5–5 t (3.9–5.5 short tons).[114][112][113] Such parameters make it the largest rhino of the Quaternary.[114] Woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) of the same time reached 1,100–1,500 kg (2,400–3,300 lb)[115] or 2,000 kg (4,400 lb),[116][117] 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in) at the shoulder height and 4.6 m (15 ft) in length.[118]

- Metamynodon, an amynodontid, reached 4 m (13 ft) in length, comparable to Hippopotamus in measurement and shape.[119]

- The giant tapir (Tapirus augustus) was the largest tapir ever, at about 623 kg (1,373 lb)[120] and 1 m (3.3 ft) tall at the shoulders.[121] Earlier, this mammal was estimated even bigger, at 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall, and assigned to the separate genus Megatapirus.[121]

- One of the biggest chalicotheres was Moropus.[122] It stood about 2.4 metres (8 ft) tall at the shoulder.[123]

- Late Eocene perissodactyls from the family Brontotheriidae attained huge sizes. The North American Megacerops (also known as Brontotherium[124]) reached 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) tall at the shoulders,[125] 5 m (16 ft) in length,[124] and 3 t (6,600 lb) in weight.[126] Embolotherium from Asia was equal in size.[127]

- The largest prehistoric horse was Equus giganteus of North America. It was estimated to grow to more than 1,250 kg (1.38 short tons) and 2 m (6 ft 7 in) at the shoulders.[128] The largest anchitherine equid was Hypohippus at 403 to 600 kg (888 to 1,323 lb), comparable to large modern domestic horses.[129][130] Megahippus is another large anchitheriine. With the body mass of 266.2 kg (587 lb) it was much heavier than most of its close relatives.[129]

Phenacodontids (Phenacodontidae)

The largest known phenacodontid is Phenacodus. It was 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) long[131] and weighed up to 56 kg (123 lb).[132]

Dinoceratans (Dinocerata)

The largest known dinoceratan was Eobasileus with skull length of 102 cm (40 in), 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) tall at the back and 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder.[133] Another huge animal of this group was Uintatherium, with skull length of 76 cm (30 in), 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder,[133] 4 m (13 ft) in length and 2.25 t (2.48 short tons), the size of a rhinoceros.[134] Despite their large size, Eobasileus as well as Uintatherium had a very small brain.[133][134]

Carnivores (Carnivora)

Caniformia

- The largest terrestrial mammalian carnivore and the largest known bear, as well as the largest known mammalian land predator of all time, was Arctotherium angustidens, the South American short-faced bear. A humerus of A. angustidens from Buenos Aires indicates that the males of the species could have weighed 1,588–1,749 kg (3,501–3,856 lb) and stood at least 3.4 m (11 ft) tall on their hind-limbs.[135][136] Another huge bear was the giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), with the average weight of 625 kg (1,378 lb) and the maximum recorded at 957 kg (2,110 lb).[137] There is a guess that the largest individuals of this species could reached even larger mass, up to 1,200 kg (2,600 lb).[138] The extinct cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) was also heavier than many recent bears. Largest males weighed as much as 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[139] Ailuropoda baconi from the Pleistocene was larger than the modern giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca).[140]

- The biggest odobenid and one of the biggest pinnipeds to have ever existed is Pontolis magnus, with skull length of 60 cm (24 in) (twice as large as the skulls of modern male walruses)[141] and more than 4 m (13 ft) in total body length.[142][143] Only the modern males of elephant seals (Mirounga) reaches the similar sizes.[142] The second largest prehistoric pinniped is Gomphotaria pugnax with the skull length of nearly 47 cm (19 in).[141]

- One of the largest of prehistoric otariids is Thalassoleon, comparable in size to the biggest extant fur seals. An estimated weight of T. mexicanus is no less than 295–318 kg (650–701 lb).[144]

- The biggest known mustelid to ever exist was likely the giant otter, Enhydriodon. It exceeded 3 m (9.8 ft) in length, and would have weighed in at around 200 kg (440 lb), much larger than any other known mustelid, living or extinct.[145][146][147] There were other giant otters, like Siamogale, at around 50 kg (110 lb)[148] and Megalenhydris, which was larger than a modern-day giant river otter.[149] Megalictis was the largest purely terrestrial mustelid[150] (although Enhydriodon had recently been mentioned as the largest mustelid that also happens to be a terrestrial predator[145]). Similar in size to the jaguar, Megalictis ferox had even wider skull, almost as wide as of the black bear.[150] Megalictis had a powerful bite force, allowing it to eat large prey and crush bones, as modern hyenas and jaguars can.[150] Another large-bodied mustelid was the superficially cat-like Ekorus from the Miocene of Africa. At almost 44 kg (97 lb), the long-legged Ekorus was about the size of a wolf[151] and filling a similar to leopards ecological niche before big cats came to the continent.[152] Other huge mustelids include Perunium[153] and hypercarnivorous Eomellivora, both from the Late Miocene.[154]

- The heaviest procyonid was possibly South American Chapalmalania. It reached 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in body length with a short tail and 150 kilograms (330 lb), comparable in size to an American black bear (Ursus americanus).[155] Another huge procyonid was Cyonasua, which weighted about 15–25 kg (33–55 lb), about the same size as a medium-sized dog.[156]

- The largest canid of all time was Epicyon haydeni, which stood 90 cm (35 in) tall at the shoulder, had a body length of 2.4 m (7.9 ft) and weighed 100–125 kg (220–276 lb),[157][158][159] with the heaviest known specimen weighing up to 170 kg (370 lb).[41] The extinct dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) reached 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in length and weighed between 50 and 110 kg (110 and 243 lb).[41][160] The largest wolf (Canis lupus) subspecies ever existed in Europe is the Canis lupus maximus from the Late Pleistocene of France. Its long bones are 10% larger than those of extant European wolves and 20% longer than those of C. l. lunellensis.[161] The Late Pleistocene Italian wolf was morphometrically close to C. l. maximus.[162]

- The largest bear-dog was a species of Pseudocyon weighing around 773 kg (1,704 lb), representing a very large individual.[163]

Feliformia

- The largest nimravid was probably Quercylurus major as its fossils suggest it was similar in size to the modern-day brown bear and was scansorial.[164] In 2021, Eusmilus was declared as the largest of the holplophonine nimravids, reaching the weight of nearly 111 kg (245 lb), comparable to a small African lion.[165] However, the largest Hoplophoneus was estimated at 160 kg (350 lb).[41]

- The biggest saber-toothed cats are Amphimachairodus kabir and Smilodon populator, with the males possibly reaching 350–490 kg (770–1,080 lb) and 220–450 kg (490–990 lb) respectively.[41][166][167] Another contender for the largest felid of all time is Machairodus. M. horribilis from China was estimated at 405 kg (893 lb)[168] while the North American M. lahayishupup weighed up to 410 kg (900 lb).[169][170][171] Xenosmilus was also a huge cat. It reached around 2 m (6.6 ft) long[172] and weighed around 300–350 kg (660–770 lb).[168]

- The heaviest known pantherine felids are the Ngangdong tiger (Panthera tigris soloensis), which are estimated to have weighed up to 486 kg (1,071 lb),[167] the American lion (Panthera atrox), weighing up to 363 kg (800 lb)[173][174] and the Eurasian cave lion (Panthera spelaea), weighing up to 339 kg (747 lb).[167] Being the ancestor of the modern jaguar,[175] Panthera gombaszoegensis was much larger, up to 150 kg (330 lb) in maximum weight.[175]

- Some extinct feline felids also surpassed their modern relatives in size. The Eurasian giant cheetah (Acinonyx pardinensis) reached 60–121 kg (132–267 lb), approximately twice as large as the modern cheetah.[176] The North American Pratifelis was larger than the extant cougar.[177]

- The largest barbourofelid was Barbourofelis fricki, with the shoulder height of 90 cm (35 in).[178]

- The largest viverrid known to have existed is Viverra leakeyi, which was around the size of a wolf or small leopard at 41 kg (90 lb).[179]

- The largest known fossil hyena is Pachycrocuta, estimated at 90–100 cm (35–39 in) at the shoulder[180] and 190 kg (420 lb) weight.[41] Another huge hyena with mass over 100 kg (220 lb) is the cave hyena. It is actually a subspecies of the African spotted hyena, which is at 10% smaller than the extinct cave hyena.[181]

- The percrocutid feliform, Dinocrocuta, was two or even three times as large as the extant spotted hyena, 160 or 240 kg (350 or 530 lb).[182]

- The extinct giant fossa (Cryptoprocta spelea) had a body mass in range from 17 kg (37 lb)[183] to 20 kg (44 lb),[184] much larger than the modern fossa weighs (up to 8.6 kg (19 lb) for adult males[185]).

Hyaenodonts (Hyaenodonta)

The largest hyaenodont was Simbakubwa at 1,500 kg (3,300 lb).[186] Another giant hyaenodont, Megistotherium reached 500 kg (1,100 lb)[41] and had a skull of 66.4 cm (26.1 in) in length.[187]

Oxyaenids (Oxyaenidae)

The largest known oxyaenid was Sarkastodon weighing in at 800 kg (1,800 lb).[41]

Mesonychians (Mesonychia)

Some mesonychians reached a size of a bear. Such large were Mongolonyx from Asia[188] and Ankalagon from North America.[189][190] Another large mesonychian is Harpagolestes with a skull length of a half a meter in some species.[188]

Bats (Chiroptera)

Found in Quaternary deposits of South and Central Americas, Desmodus draculae had a wingspan of 0.5 m (20 in) and a body mass of up to 60 g (2.1 oz). Such proportions make it the largest vampire bat that ever evolved.[191]

Hedgehogs, gymnures, shrews, and moles (Eulipotyphla)

The largest known animal of the group Eulipotyphla was Deinogalerix,[192] measuring up to 60 cm (24 in) in total length, with a skull up to 21 cm (8.3 in) long.[193]

Rodents (Rodentia)

- Several of the extinct South American dinomyids were much bigger than the modern rodents. Josephoartigasia monesi was the largest-known rodent of all time, approximately weighing an estimated 480–500 kg (1,060–1,100 lb).[194] Phoberomys pattersoni weighed 125–150 kg (276–331 lb).[194] Both Josephoartigasia and Phoberomys reached about 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall at the shoulder.[195] Another huge dinomyid, Telicomys gigantissimus had a minimal weight of 200 kg (440 lb).[195]

- Amblyrhiza inundata from the family Heptaxodontidae was a massive animal, it weighed 50–200 kg (110–440 lb).[196][195]

- The largest beaver was the giant beaver (Castoroides) of North America. It grew over 2 m in length and weighed roughly 90 to 125 kg (198 to 276 lb), also making it one of the largest rodents to ever exist.[197]

Rabbits, hares, and pikas (Lagomorpha)

The biggest known prehistoric lagomorph is Minorcan giant lagomorph Nuralagus rex at 12 kg (26 lb).[198]

Primates (Primates)

- The largest known primate as well as the largest hominid of all time was Gigantopithecus blackii, standing 3 m (9.8 ft) tall and weighing 540 kg (1,200 lb).[199][200] However In 2017, new studies suggested a body mass of 200–300 kg (440–660 lb) for this primate.[201] Another giant hominid was Meganthropus palaeojavanicus at 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) in body height,[202] although it is known from very poor remains.[203]

- During the Pleistocene, some archaic humans were close in sizes or even larger than early modern humans. Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) reached 77.6 kg (171 lb) and 66.4 kg (146 lb) in average weight for males and females, respectively, larger than the parameters of modern humans (Homo sapiens) (68.5 kg (151 lb) and 59.2 kg (131 lb) for males and females, respectively).[204] A tibia from Kabwe (Zambia) indicates an indeterminate Homo individual of possibly 181.2 cm (71.3 in) in height. It was one of the tallest humans of the Middle Pleistocene and noticeably large even compared to recent humans.[205] The tallest Homo sapiens individuals from the Middle Pleistocene of Spain reached 194 cm (76 in) and 174 cm (69 in) for males and females, respectively.[205] Some Homo erectus could be as large as 185 cm (73 in) tall and 68 kg (150 lb) in weight.[206][207]

- The largest known Old World monkey is the prehistoric baboon, with a male specimen of Dinopithecus projected to weigh an average of 46 kg (101 lb) and up to 57 kg (126 lb).[208] It exceeds the maximum weight record of the chacma baboon, the largest extant baboon. One source projects a specimen of Theropithecus oswaldi to have weighed 72 kg (159 lb).[209]

- The largest known New World monkey was Cartelles, which is studied as specimen of Protopithecus, weighing up to 34.27 kg (75.6 lb). Caipora bambuiorum is another large species, weighing up to 27.74 kg (61.2 lb).[210]

- The largest omomyids were Macrotarsius and Ourayia from the Middle Eocene. Both reached 1.5–2 kg (3.3–4.4 lb) in weight.[211]

- Some prehistoric lemuriform primates grew to huge sizes as well. Archaeoindris was a 1.5-metre-long (4.9 ft) sloth lemur that lived in Madagascar and weighed 150–187.8 kg (331–414 lb),[212] as large as an adult male gorilla.[213] Palaeopropithecus from the same family was also heavier than most modern lemurs, at 25.8–45.8 kg (57–101 lb).[214] Megaladapis is another large extinct lemur at 1.3 to 1.5 m (4 ft 3 in to 4 ft 11 in) in length[citation needed] and an average body mass of around 140 kg (310 lb).[215] Other estimates suggest 46.5–85.1 kg (103–188 lb) but its still much larger than any extant lemur.[214]

Elephants, mammoths, and mastodons (Proboscidea)

- The largest known land mammal ever was a proboscidean called Palaeoloxodon namadicus which weighed about 22 t (24.3 short tons) and measured about 5.2 m (17.1 ft) tall at the shoulder.[110] The largest individuals of the steppe mammoth of Eurasia (Mammuthus trogontherii) estimated to reach 4.5 m (14.8 ft) at the shoulders and 14.3 t (15.8 short tons) in weight.[110][216] Stegodon zdanskyi, the biggest species of Stegodon, was 13 t (14.3 short tons) in body mass.[110] Another one enormous proboscidean is Stegotetrabelodon syrticus, over 4 m (13 ft) in height and 11 to 12 t (12.1 to 13.2 short tons) in weight.[110] The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) was about 4 m (13.1 ft) tall at the shoulder but didn't weigh as much as other huge mammoths. Its average mass was 9.5 t (10.5 short tons) with one unusually large specimen about 12.5 t (13.8 short tons).[110] Columbian mammoths had very long tusks. The largest known mammoth tusk, 4.9 m (16 ft) long, belonged to this species.[217]

- The largest mammutid was the Neogene Mammut borsoni. The biggest specimen reached 4.1 m (13 ft) tall and weighed about 16 t (17.6 short tons).[110] This species also had the longest tusks, 5.02 m (16.5 ft) long from basis to tip along the curve.[218]

- Deinotherium was the largest proboscidean in Deinotheriidae family. Bones retrieved in Crete confirm the existence of specimen 4.1 m (13 ft) tall at the shoulders and more than 14 t (15.4 short tons) in weight.[110]

Sea cows (Sirenia)

According to reports, Steller's sea cows have grown to 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft) long as adults, much larger than any extant sirenians.[219] The weight of Steller's sea cows is estimated to be 8–10 t (8.8–11.0 short tons).[220]

Arsinoitheres (Arsinoitheriidae)

The largest known arsinoitheriid was Arsinoitherium. A. zitteli would have been 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) tall at the shoulders, and 3 m (9.8 ft) long.[221][222] A. giganteum reached even larger size than A. zitteli.[223]

Hyraxes (Hyracoidea)

Some of the prehistoric hyraxes were extremely large compared to modern small relatives. The largest hyracoid ever evolved is Titanohyrax ultimus.[224] With the mass estimation in rage of 600 kg (1,300 lb) to over 1,300 kg (2,900 lb) it was close in size to Sumatran rhinoceros.[225] Another enormous hyrax is Megalohyrax which had skull of 391 mm (15.4 in) in length[226] and reached the size of tapir.[227][224] More recent Gigantohyrax was three times as large as the extant relative Procavia capensis,[228] although it is noticeably smaller than earlier Megalohyrax and Titanohyrax.[229]

Desmostylians (Desmostylia)

The largest known desmostylian was a species of Desmostylus, with skull length of 81.8 cm (32.2 in) and comparable in size to the Steller's sea cow.[230]

Paleoparadoxia is also known as one of the largest desmostylians, with body length of 3.03 m (9.9 ft).[231]

Armadillos, glyptodonts and pampatheres (Cingulata)

The largest cingulate known is Doedicurus, at 4 m (13 ft) long, 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) high[134] and reaching a mass of approximately 1,910 to 2,370 kg (2.11 to 2.61 short tons).[citation needed] The largest species of Glyptodon, Glyptodon clavipes, reached 3–3.3 m (9.8–10.8 ft) in length[232][134] and 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight.[citation needed]

Anteaters and sloths (Pilosa)

The largest known pilosan ever was Megatherium, a ground sloth with an estimated average weight of 3.8 t (4.2 short tons)[233] and a height of 6 m (20 ft)[233] which is almost as big as the African bush elephant. Several other sloths grew to large sizes as well, such as Eremotherium, but none as large as Megatherium.

Astrapotherians (Astrapotheria)

Some of the largest known astrapotherians weighed about 3–4 t (3.3–4.4 short tons), including the genus Granastrapotherium[234] and some species of Parastrapotherium (P. martiale).[235] The skeleton remains suggests that the species Hilarcotherium miyou was even larger, with a weight of 6.456 t (7.117 short tons).[236]

Litopterns (Litopterna)

The largest known litoptern was Macrauchenia, which had three hoofs per foot. It was a relatively large animal, with a body length of around 3 m (9.8 ft).[237]

Notoungulates (Notoungulata)

The largest notoungulate known of complete remains is Toxodon. It was about 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) in body length, and about 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) high at the shoulder and resembled a heavy rhinoceros. Although is not complete, the preserved fossils suggests that Mixotoxodon were the most massive member of the group, with a weight about 3.8 t (4.2 short tons).[238]

Pyrotherians (Pyrotheria)

The largest mammal of the South American order Pyrotheria was Pyrotherium at 2.9–3.6 m (9 ft 6 in – 11 ft 10 in) in length and 1.8–3.5 t (4,000–7,700 lb) in weight.[239]

Reptiles (Reptilia)

Lizards and snakes (Squamata)

- Giant mosasaurs are the largest-known animals within the Squamata. The largest-known mosasaur is likely Mosasaurus hoffmanni, estimated at more than 17 m (56 ft) in length,[240][241] however these estimations are based on heads and total body length ratio 1:10, which is unlikely for Mosasaurus, and probably that ratio is about 1:7.[242] Another giant mosasaur is Tylosaurus, estimated at 10–14 m (33–46 ft) in length.[243][244] Another large mosasaur is Hainosaurus bernardi (could be synonymous to Tylosaurus). It was once estimated at 17 and 15 m (56 and 49 ft) in length,[245][246] but later estimates put it at around 12.2 m (40 ft).[247]

- The largest known prehistoric snake is Titanoboa cerrejonensis, estimated at 12.8 m (42 ft) in length and 1,135 kg (2,502 lb) in weight.[248] Another known very large fossil snake is Gigantophis garstini, estimated at 9.3–10.7 m (31–35 ft) in length,[249][250] although later study shows smaller estimation about 6.6–7.2 m (22–24 ft).[251] A close rival in size to Gigantophis is a fossil snake, Palaeophis colossaeus, which may have been around 9 m (30 ft) in length.[248][252][253] Later studies speculate that it reached a maximum length of 12.3 m (40 ft).[254] The largest fossil python is Liasis dubudingala with length roughly 9 m (30 ft).[255] The largest viper as well as the largest venomous snake ever recorded is Laophis crotaloides from the Early Pliocene of Greece. This snake reached over 3 m (9.8 ft) in length and 26 kg (57 lb) in weight.[256][257] Another huge fossil viper is indeterminate species of Vipera. With a length of around 2 m (6 ft 7 in) it was one of the biggest predators of Mallorca during the Early Pliocene.[258] The largest known blind snake is Boipeba tayasuensis with estimated total length of 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in).[259]

- The largest known land lizard is probably megalania (Varanus priscus) at 7 m (23 ft) in length.[260] As extant relatives, megalania could have been venomous and in that case this lizard was also the largest venomous vertebrate ever evolved.[261] However, maximum size of this animal is subject to debate.[262]

Turtles, tortoises and close relatives (Pantestudines)

Cryptodira

- The largest known turtle ever was Archelon ischyros at 5 m (16 ft) long and 2,200 kg (4,900 lb).[263] Possible second-largest sea turtle was Protostega at 3.9 m (13 ft) in total body length.[264][265] There is even a larger specimen of this genus from Texas estimated at 4.2 m (14 ft) in total length.[266][264] Another huge prehistoric sea turtle is the Late Cretaceous Gigantatypus, estimated at over 3.5 m (11 ft) in length.[267] Psephophorus terrypratchetti from the Eocene attained 2.3–2.5 m (7.5–8.2 ft) in body length.[268]

- The largest tortoise was Megalochelys atlas at up to 2.7 m (9 ft) in shell length[269] and weighing 0.8–1.0 t (1,800–2,200 lb).[126] M. margae had carapace of 1.4–2 m (4.6–6.6 ft) long; an unnamed species from Java reached at least 1.75 m (5.7 ft) in carapace length.[270] The Cenozoic Titanochelon were also larger than extant giant tortoises, with a shell length of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in).[271][272] Other giant tortoises include Centrochelys marocana at 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) in carapace length and Mesoamerican Hesperotestudo sp. at 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in carapace length.[270]

- The largest trionychid ever recorded is indeterminate specimen GSP-UM 3019 from the Middle Eocene of Pakistan. Bony carapace of GSP-UM 3019 is 120 cm (3.9 ft) long and 110 cm (3.6 ft) wide indicates the total carapace diameter (with soft margin) about 2 m (6.6 ft).[273] Drazinderetes tethyensis from the same formation had a bony carapace 80 cm (2.6 ft) long and 70 cm (2.3 ft) wide.[273] Another huge trionychid is North American Axestemys byssinus at over 2 m (6.6 ft) in total length.[274]

Side-necked turtles (Pleurodira)

The largest freshwater turtle of all time was the Miocene podocnemid Stupendemys, with an estimated parasagittal carapace length of 2.86 m (9 ft 5 in) and weight of up to 1,145 kg (2,524 lb).[275] Carbonemys cofrinii from the same family had a shell that measured about 1.72 m (5 ft 8 in),[276][277][278] complete shell was estimated at 1.8 m (5.9 ft).[279]

Macrobaenids (Macrobaenidae)

The largest macrobaenids were the Early Cretaceous Yakemys, Late Cretaceous Anatolemys, and Paleocene Judithemys. All reached 70 cm (2.3 ft) in carapace length.[280]

Meiolaniformes

The largest meiolaniid was Meiolania. Meiolania platyceps had a carapace 100 cm (3.3 ft) long[270] and probably reached over 3 m (9.8 ft) in total body length.[281] An unnamed Late Pleistocene species from Queensland was even larger, up to 200 cm (6.6 ft) in carapace length.[270] Ninjemys oweni reached 100 cm (3.3 ft) in carapace length[270] and 200 kg (440 lb) in weight.[282]

Sauropterygians (Sauropterygia)

Placodonts and close relatives (Placodontiformes)

Placodus was among the largest placodonts, with a length of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[283]

Nothosaurs and close relatives (Nothosauroidea)

The largest nothosaur as well as the largest Triassic sauropterygian was Nothosaurus giganteus at 7 m (23 ft) in length.[284]

Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria)

- The largest known plesiosauroid was Aristonectes, with a body length of 10–11.86 metres (32.8–38.9 ft) and body mass of 4 t (4.4 short tons)[285] or even 10.7–13.5 t (11.8–14.9 short tons).[286] Another long plesiosauroid was Albertonectes at 11.2–11.6 metres (37–38 ft).[287] Thalassomedon rivaled it in size, with its length at 10.86–11.6 m (35.6–38.1 ft).[288] Other large plesiosauroids are Styxosaurus and Elasmosaurus. Both reached some more than 10 m (33 ft) in length.[285][289] Hydralmosaurus (previously synonymized with Elasmosaurus and Styxosaurus) reached 9.44 m (31.0 ft) in total body length.[289] In past, Mauisaurus was considered to be more than 8 m (26 ft) in length,[290][289] but later it was determined as nomen dubium.[291]

- There is much controversy over the largest-known of the Pliosauroidea. Pliosaurus funkei, fossil remains of a pliosaur nicknamed as "Predator X" have been discovered and excavated from Norway in 2008. This pliosaur has been estimated at 10–13 m (33–43 ft) in length.[292] However, in 2002, a team of paleontologists in Mexico discovered the remains of a pliosaur nicknamed as "Monster of Aramberri", which is also estimated at 15 m (49 ft) in length,[293] with shorter estimation about 11.5 m (38 ft).[294] This species is, however, claimed to be a juvenile and has been attacked by a larger pliosaur.[295] Some media sources claimed that Monster of Aramberri was a Liopleurodon but its species is unconfirmed thus far.[293] Another very large pliosaur was Pliosaurus macromerus, known from a single 2.8-metre-long (9.2 ft) incomplete mandible.[296] The Early Cretaceous Kronosaurus queenslandicus is estimated at 9–10.9 m (30–36 ft) in length and 10.6–12.1 t (11.7–13.3 short tons) in weight.[297][298] The Late Jurassic Megalneusaurus rex could reach lengths of 7.6–9.1 metres (25–30 ft).[299][300] Close contender in size was the Late Cretaceous Megacephalosaurus eulerti with a length in range of 6–9 m (20–30 ft).[301]

Proterosuchids (Proterosuchidae)

Proterosuchus fergusi is the largest known proterosuchid with a skull length of 47.7 cm (18.8 in) and a possible body length of 3.5–4 m (11–13 ft).[302]

Erythrosuchids (Erythrosuchidae)

The largest erythrosuchid was Erythrosuchus africanus with a maximum length of 4.75–5 m (15.6–16.4 ft).[303]

Phytosaurs (Phytosauria)

Some of the largest known phytosaurs include Redondasaurus with a length of 6.4 m (21 ft)[304] and Smilosuchus with a length of more than 7 m (23 ft).[305]

Non-crocodylomorph pseudosuchians (Pseudosuchia)

- The largest shuvosaurid and one of the largest pseudosuchian from the Triassic period was Sillosuchus. Biggest specimens could have reached 9–10 m (30–33 ft) in length.[306][307]

- The largest known carnivorous pseudosuchian of the Triassic is loricatan Fasolasuchus tenax, which measured an estimated of 8 to 10 m (26 to 33 ft).[308][306][307] It is both the largest "rauisuchian" known to science, and the largest non-dinosaurian terrestrial predator ever discovered.[citation needed] Biggest individuals of Postosuchus[309] and Saurosuchus[310] had a body length of around 7 m (23 ft). A specimen of Prestosuchus discovered in 2010 suggest that this animal also reached lengths of nearly 7 m (23 ft) making it one of the largest Triassic pseudosuchians.[311]

- Desmatosuchus was likely one of the largest known aetosaurs, about 4–6 m (13–20 ft) in length and 280 kg (620 lb) in weight.[312][313][314]

Crocodiles and close relatives (Crocodylomorpha)

Aegyptosuchids (Aegyptosuchidae)

The Late Cretaceous Aegisuchus is the main contender for the title of the largest crocodylomorph ever recorded. It reached 15 m (49 ft) in length by the lower estimate and as much as 22 m (72 ft) by the upper estimate,[315] although a length of over 15 m is likely an overestimate.[315]

Crocodylians (Crocodylia)

- The largest caiman and likely the largest crocodylian was Purussaurus brasiliensis estimated at 11–13 m (36–43 ft).[316] According to another information, maximum estimate measure 11.4 m (37 ft) and almost 7.8 t (8.6 short tons) in length and in weight respectively.[317] Another giant caiman was Mourasuchus. Various estimates suggest the biggest specimens reached 9.47 m (31.1 ft) in length and 8.5 t (9.4 short tons) in weight[318] or 4.7–5.98 m (15.4–19.6 ft) in body length.[319]

- The largest alligatoroid is likely Deinosuchus riograndensis at 12 m (39 ft) long and weighing 8.5 t (9.4 short tons).[320][321]

- The largest extinct species of the genus Alligator was the Haile alligator (Alligator hailensis), which had a skull 52.5 cm (20.7 in) long and was similar in size to the extant American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis).[322]

- The largest gavialids were Asian Rhamphosuchus at 8–11 m (26–36 ft)[323][324][317] and South American Gryposuchus at 10.15 m (33.3 ft) in length.[325][324]

- The basal crocodyloidean Astorgosuchus bugtiensis from the Oligocene was large. It estimated at 8 m (26 ft) in length.[324]

- The largest known true crocodile was Euthecodon which estimated to have reached 6.4–8.6 m (21–28 ft) or even 10 m (33 ft) long.[326][317] The largest species of the modern Crocodylus were Kenyan Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni at 7.56 m (24.8 ft) in length,[327][317] Tanzanian Crocodylus anthropophagus at 7.5 m (25 ft) in length[328][329] and indeterminate species from Kali Gedeh (Java) at 6–7 m (20–23 ft) in length.[330]

- Unnamed Pliocene species of Quinkana known from partial remains may have reached up to 6 m (20 ft) in length, although other species (known from Oligocene to Pleistocene) are smaller with length just about 3 m (9.8 ft). It is not only the largest mekosuchian (some studies reject it from this group[331]) but also it could have been Australia's largest Pliocene predator.[260] Paludirex is another large mekosuchian with length over 4 m (13 ft).[332]

Paralligatorids (Paralligatoridae)

The largest paralligatorid was likely Kansajsuchus estimated at up to 8 m (26 ft) long.[333]

Tethysuchians (Tethysuchia)

- Some extinct pholidosaurids reached giant sizes. In the past, the Sarcosuchus imperator was believed to be the largest crocodylomorph, with initial estimates proposing a length of 12 m (39 ft) and a weight of 8 t (8.8 short tons).[334] However, recent estimates have now shrunk to a length of 9 to 9.5 m (29.5 to 31.2 ft) and a weight of 3.5 to 4.3 metric tons (3.9 to 4.7 short tons).[335] Related to Sarcosuchus, Chalawan thailandicus could reached more than 10 m (33 ft) in length,[336] although other estimates suggest 7–8 m (23–26 ft).[324]

- The largest dyrosaurid was Phosphatosaurus gavialoides estimated at 9 m (30 ft) in length.[337][324]

Stomatosuchids (Stomatosuchidae)

Stomatosuchus, a stomatosuchid, estimated at 10 m (33 ft) in length.[338]

Notosuchians (Notosuchia)

- The largest terrestrial notosuchian crocodylomorph was very likely the Miocene sebecid Barinasuchus, with a skull of 95–110 cm (37–43 in) long, comparable in size to the 104 cm (41 in)-long skull of Daspletosaurus.[339] Various estimates suggest a possible length of Barinasuchus at 6–7.5 m (20–25 ft).[339]

- Other huge notosuchians are Brazilian Stratiotosuchus at 4 m (13 ft) long,[340] and Baurusuchus at 3.5–4 m (11–13 ft) long,[341] both from the family Baurusuchidae.[340]

Thalattosuchians (Thalattosuchia)

- The largest thalattosuchian as well as the largest teleosauroid was the Early Cretaceous Machimosaurus rex estimated at 7.15 m (23.5 ft) in length.[342] Neosteneosaurus edwardsi (previously known as Steneosaurus edwardsi[343]) was the biggest Middle Jurassic crocodylomorph, it reached 6.6 m (22 ft) long.[342]

- Plesiosuchus was very large metriorhynchid. With the length of 6.83 m (22.4 ft) it exseeded even some pliosaurids of the same time and locality such as Liopleurodon.[344] Other huge metriorhynchids include Tyrannoneustes at 5 m (16 ft) in length[345] and Torvoneustes at 4.7 m (15 ft) in length.[346]

Basal crocodylomorphs

Redondavenator was the largest Triassic crocodylomorph ever recorded,[347] with a skull of at least 60 cm (2.0 ft) in length.[348][349] Another huge basal crocodylomorph was Carnufex[347] at 3 m (9.8 ft) long even through that is immature.[350]

Pterosaurs (Pterosauria)

- The largest known pterosaur was Quetzalcoatlus northropi, at 127 kg (280 lb) and with a wingspan of 10–12 m (33–39 ft).[351] Another close contender is Hatzegopteryx, also with a wingspan of 12 m (39 ft) or more.[351] This estimate is based on a skull 3 m (9.8 ft) long.[352] Yet another possible contender for the title is Cryodrakon which had a 10-metre (33 ft) wingspan.[353] An unnamed pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Nemegt Formation could reach a wingspan of nearly 10 m (33 ft).[354][355] According to various assumptions, the wingspan of Arambourgiania philadelphiae reached from 8 m (26 ft) to more than 10 m (33 ft).[354][353] South American Tropeognathus reached the maximum wingspan of 8.7 m (29 ft).[356][357]

- The largest of non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs as well as the largest Jurassic pterosaur[358] was Dearc, with an estimated wingspan between 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) and 3.8 m (12 ft).[359] Only a fragmentary rhamphorhynchid specimen from Germany could be larger (184% the size of the biggest Rhamphorhynchus).[360] Other large non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs were Sericipterus, Campylognathoides and Harpactognathus, with the wingspan of 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in),[361] 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in),[361] and 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in),[360] respectively.

Choristoderes (Choristodera)

The largest known choristoderan, Kosmodraco dakotensis (previously known as Simoedosaurus dakotensis[362]) is estimated to have had a total length of around 5 m (16 ft).[363][362]

Tanystropheids (Tanystropheidae)

Tanystropheus, the largest of all tanystropheids, reached up to 5 m (16 ft) in length.[364]

Thalattosaurs (Thalattosauria)

The largest species of thalattosaur, Miodentosaurus brevis grew to more than 4 m (13 ft) in length.[365] The second largest member of this group is Concavispina with a length of 3.64 m (11.9 ft).[366]

Ichthyosaurs (Ichthyosauria)

The largest known ichthyosaur and the largest marine reptile was the Late Triassic Shastasaurus sikanniensis at 21 m (69 ft) in length[367][368] and 81.5 t (180,000 lb) in weight.[369] In April 2018, paleontologists announced the discovery of a previously unknown ichthyosaur that may have reached lengths of 26 m (85 ft) making it one of the largest animals known, rivaling some blue whales in size.[370][371] Another, larger ichthyosaur was found in 1850 in Aust.[372] Its remains seemed to surpass the measurements of the other ichthyosaur, but the researchers commented that the remains were too fragmentary for a size estimate to be made.[372] Another huge ichthyosaur was Shonisaurus popularis at 15 m (49 ft) in length and 29.7 t (65,000 lb) in weight.[368] The largest Middle Triassic ichthyosaur as well as the largest animal of that time was Cymbospondylus youngorum at 14 to 17.65 m (45.9 to 57.9 ft) in length[373][369] and 14.7 to 135.8 t (32,000 to 299,000 lb) in weight.[369]

Tangasaurids (Tangasauridae)

The largest tangasaurid was Hovasaurus with an estimated snout-vent length of 30–35 cm (12–14 in) and a tail of 60 cm (24 in).[374]

Pareiasaurs (Pareiasauria)

Largest pareiasaurs reached up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length. Such sizes had Middle Permian Bradysaurus, Embrithosaurus, and Nochelesaurus from South Africa,[375] and the Late Permian Scutosaurus from Russia.[375] The most robust Scutosaurus had 1.16 t (2,600 lb) in body mass.[375]

Captorhinids (Captorhinidae)

The heavy built Moradisaurus grandis, with a length of 2 m (6 ft 7 in),[376] is the largest known captorhinid.[377] The second largest captorhinid was Labidosaurikos with the largest adult skull specimen 28 cm (11 in) long.[378]

Non-avian dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

Sauropodomorphs (Sauropodomorpha)

The largest of non-sauropod sauropodomorphs ("prosauropod") was Euskelosaurus. It reached 12.2 m (40 ft) in length and 2 t (2.2 short tons) in weight.[379] Another huge sauropodomorph Yunnanosaurus youngi reached 13 m (43 ft) long.[380]

Sauropods (Sauropoda)

- A mega-sauropod, Maraapunisaurus fragillimus (previously known as Amphicoelias fragillimus), is a contender for the largest-known dinosaur in history. It has been estimated at 58–60 m (190–197 ft) in maximum length and 122,400 kg (269,800 lb) in weight.[381] Unfortunately, the fossil remains of this dinosaur have been lost.[381] More recently, it was estimated at 35–40 m (115–131 ft) in length and 80–120 t (180,000–260,000 lb) in weight.[382]

- Known from the incomplete and now disintegrated remains, the Late Cretaceous Bruhathkayosaurus matleyi was an anomalously large sauropod.[383] Informal estimations suggested as huge parameters as 45 m (148 ft) in length and 139–220 t (306,000–485,000 lb) in weight.[384] More accurate estimation suggests 37 m (121 ft) and 95 t (209,000 lb) but it still much heavier than most other sauropods.[384]

- BYU 9024, a massive cervical vertebra found in Utah,[385] may belong to Barosaurus lentus[386][387] or Supersaurus vivianae[388] of a huge size, possibly 45–48 m (148–157 ft) in length and 60–66 t (132,000–146,000 lb) in body mass.[389][387] Supersaurus vivianae itself may have been the longest dinosaur yet discovered as a study of 3 specimens suggested length of 39 m (128 ft) or over 40 m (130 ft).[388]

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum was likely the largest mamenchisaurid, reaching nearly 35 m (115 ft) in length and 60–80 t (130,000–180,000 lb) in weight.[382] Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis from the same family had 15 m (49 ft)-long neck, about 55% of its total length that could be at least 27 m (89 ft).[390]

- The Middle Jurassic Breviparopus taghbaloutensis was mentioned in The Guinness Book of Records as the longest dinosaur at 48 m (157 ft) although this animal is known only from fossil tracks.[391][392] Originally thought to be a brachiosaurid, it was later identified as a huge diplodocoid, possibly 33.5 m (110 ft) in length and 62 t (137,000 lb) in weight.[393]

- The tallest sauropod was Sauroposeidon proteles with estimated height at 16.5–18 m (54–59 ft).[394][395][396] Asiatosaurus could reach 17.5 m (57 ft) in height but this animal is known only from teeth.[396] Giraffatitan was estimated at 16 m (52 ft) in height.[397]

Other huge sauropods include Argentinosaurus, Alamosaurus, and Puertasaurus with estimated lengths of 30–33 m (98–108 ft) and weights of 50–80 t (55–88 short tons).[398] Patagotitan was estimated at 37 m (121 ft) in length[399] and 57 t (63 short tons) in average weight,[400] and was similar in size to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus.[401] Giant sauropods like Supersaurus, Sauroposeidon, and Diplodocus probably rivaled them in length but not in weight.[381] Dreadnoughtus was estimated at 49 t (108,000 lb) in weight[400] and 26 m (85 ft) in length but the most complete individual was immature when it died.[402] Turiasaurus is considered of being the largest dinosaur from Europe,[403][404] with an estimated length of 30 m (98 ft) and a weight of 50 t (55 short tons).[398][404] However, with lower estimate at 21 m (69 ft) and 30 t (66,000 lb) it was smaller than Portuguese Lusotitan that reached 24 m (79 ft) in length and 34 t (75,000 lb) in weight.[405]

Many large sauropods are still unnamed and may rival the current record holders:

- The "Archbishop", a large brachiosaur that was discovered in 1930. The animal was reported to get a scientific paper published by the end of 2016.[406]

- Brachiosaurus nougaredi is yet another large brachiosaur from Early Cretaceous North Africa. The remains have been lost, but the sacrum drawing remains. They suggest a sacrum of almost 1.3 m (4.3 ft) long,[407] making it the largest dinosaur sacrum discovered so far, except those of Argentinosaurus and Apatosaurus.[408]

- In 2010, the femur of a large sauropod was discovered in France. The femur suggests an animal that grew to immense sizes.[409]

Non-avian theropods (Theropoda)

- The largest theropod as well as the largest terrestrial (or possibly semi-aquatic)[410] predator yet known is Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, with the largest specimen known estimated at 12.6–18 m (41–59 ft) in length and around 7–20.9 t (8–23 short tons) in weight.[411][412] New estimates published in 2014 and 2018, based on a more complete specimen supported that Spinosaurus could reach lengths of 15 to 16 meters (49 to 52 ft).[413][414][415] The latest estimates suggest a weight of 6.4 to 7.5 metric tons (7.1 to 8.3 short tons).[414][415] The White Rock spinosaurid had vertebrae comparable in dimensions to Spinosaurus, it was likely a huge theropod with a length over 10 m (33 ft).[416]

- Other large theropods were Giganotosaurus carolinii, and Tyrannosaurus rex, whose largest specimens known estimated at 13.2 m (43 ft)[417] and 12.3 m (40 ft)[418] in length, and weigh between 4.2 to 13.8 t (4.6 to 15.2 short tons)[419][420][421][411] and 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons)[422][423] to over 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),[418] respectively. Some other notable giant theropods (e.g. Carcharodontosaurus, Acrocanthosaurus, and Mapusaurus) may also have rivaled them in size.

- Macroelongatoolithus, ranging from 34–61 cm (1.12–2.00 ft) in length,[424] is the largest known type of dinosaur egg.[425] It is assigned to oviraptorosaurs like Beibeilong.[425]

Armoured dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

The largest-known thyreophoran was Ankylosaurus at 9 m (30 ft) in length and 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons) in weight.[426][427] Stegosaurus was also 9 m (30 ft) long[404] but around 5 tonnes (5.5 short tons) tonnes in weight.[citation needed]

Pachycephalosaurs (Pachycephalosauria)

The largest pachycephalosaur was the nominate Pachycephalosaurus. Previously claimed to be at 7 m (23 ft) in length,[404] it was later estimated about 4.5 metres (14.8 ft) long and a weight of about 450 kilograms (990 lb).[428]

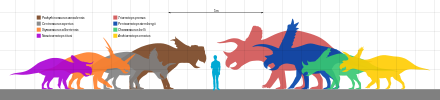

Ceratopsians (Ceratopsia)

The largest ceratopsian known is Triceratops horridus, along with the closely related Eotriceratops xerinsularis both with estimated lengths of 9 m (30 ft). Pentaceratops and several other ceratopsians rival them in size.[429] Titanoceratops had one of the longest skull of any land animal, at 2.65 m (8.7 ft) long.[430]

Ornithopods (Ornithopoda)

- The very largest known ornithopods, like Shantungosaurus were as heavy as medium-sized sauropods at up to 23 t (25 short tons),[431][432] and 16.6 m (54 ft) in length.[431] Magnapaulia reached 12.5 m (41 ft) in length,[433] or, according to original description, even 15 m (49 ft).[434][404] The Mongolian Saurolophus, S. angustirostris, reached 13 m (43 ft) long and possibly more.[435] Such animal could weighed up to 11 t (12 short tons).[435] The largest Edmontosaurus reached 12 m (39 ft) in length and around 6 t (6.6 short tons) in body mass.[436] An estimated maximum length of Brachylophosaurus is 11 m (36 ft) resulting in weight of 7 t (7.7 short tons).[437] PASAC-1, informally named "Sabinosaurus", is the largest well-known North American saurolophine,[438] around 11 m (36 ft) long, that is about 20% larger than other known specimens.[439] Hypsibema missouriensis was up to 10.7 m (35 ft) long.[440][441] The Late Cretaceous Charonosaurus was estimated around 10 m (33 ft) in length and 5 t (5.5 short tons) in weight.[404][442]

- The largest ornithopod outside of Hadrosauroidea was likely the Iguanodon. Biggest specimens reached 11 m (36 ft) in length[443][444] and weighed around 4.5 t (5.0 short tons).[445] Another large ornithopod is Iguanacolossus, with 9 m (30 ft) in length and 5 t (5.5 short tons) in weight.[446][447]

- The largest rhabdodontid was Matheronodon, estimated at 4.8 m (16 ft) in length.[448] Rhabdodon reached approximately 4 m (13 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb) according to 2016 estimates.[449]

Birds (Aves)

The largest known birds of all time might have been the elephant birds of Madagascar. Both were about 3 m (9.8 ft) tall and 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) in weight.[450] Nearly the same size was the Australian Dromornis stirtoni (see below). The tallest bird ever was the giant moa at 3.6 m (12 ft) tall.[451]

The widest known wingspan of any flight-capable bird was Pelagornis sandersi with a wingspan of 7.3 m (24 ft), and a body weight of 21.7 kg (48 lb). The heaviest flight-capable bird was the giant teratorn, Argentavis magnificens which had a somewhat-smaller wingspan at around 5.09–6.5 m (16.7–21.3 ft)[452][453] but was far heavier, with accepted maximums around 70–72 kg (154–159 lb).[454]

Enantiornitheans (Enantiornithes)

One of the largest enantiornitheans was Enantiornis,[455] with a length in life of around 78.5 cm (30.9 in), hip height of 34 cm (13 in), weight of 6.75 kg (14.9 lb),[456] and wingspan comparable to some of the modern gulls, around 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in).[455] Gurilynia was the largest Mesozoic bird from Mongolia, with a length of 53 cm (21 in), hip height of 23.2 cm (9.1 in), and weight of 2.1 kg (4.6 lb).[456]

Avisauridae

The Late Cretaceous Avisaurus was almost as large as Enantiornis. It had a wingspan around 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in),[455] a length of 72 cm (28 in), hip height of 31.5 cm (12.4 in), and weight of 5.1 kg (11 lb).[456] Even larger could be the Soroavisaurus. One tibiotarsus (PVL-4033) indicates an animal with a length of 80 cm (31 in), hip height of 35 cm (14 in), and weight of 7.25 kg (16.0 lb).[456] Mirarce was comparable in size to a turkey, much larger than most of other enantiornitheans.[457]

Pengornithidae

One of the biggest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird was Pengornis at 50 cm (1.6 ft) in length[404] and skull length of 54.7 mm (2.15 in).[458]

Gargantuaviidae

Gargantuavis is the largest known bird of the Mesozoic, a size ranging between the cassowary and the ostrich, and a mass of 140 kg (310 lb) like modern ostriches.[459] In 2019 specimens MDE A-08 and IVPP-V12325 were measured at 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) in length, 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) in hip height, and 120 kg (260 lb) in weight.[460]

Dromornithiformes

The largest dromornithid was Dromornis stirtoni over 3 m (9.8 ft) tall[461] and 528–584 kg (1,164–1,287 lb) in mass for males.[462]

Gastornid (Gastornithiformes)

Large individuals of Gastornis (also known as Diatryma) reaged up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height.[463] Weight of Gastornis ranges from 100 kg (220 lb) to 156 kg (344 lb) and sometimes to 180 kg (400 lb) for European specimens and from 160 kg (350 lb) to 229 kg (505 lb) for North American.[464][465][466]

Waterfowl (Anseriformes)

Possibly flightless, the Miocene Garganornis ballmanni was larger than any extant members of Anseriformes, with 15.3–22.3 kg (34–49 lb) in body mass.[467] Another huge anseriform was the flightless New Zealand goose (Cnemiornis). It reached 15–18 kg (33–40 lb), approaching in size to small species of moa.[468]

Swans (Cygnini)

The largest swan of ever evolved was the Pleistocene giant swan (Cygnus falconeri), it reached bill-to-tail length of about 190–210 cm (75–83 in),[469] weighed around 16 kg (35 lb) and had a wingspan of about 3 m (9.8 ft).[470][471][472] The New Zealand swan (Cygnus sumnerensis) weighed up to 10 kg (22 lb), much more than related black swan at only 6 kg (13 lb).[473] The giant Annakacygna yoshiiensis from the Miocene of Japan was much bigger than the extant mute swan.[474]

Anatinae

Finsch's duck (Chenonetta finschi) reached 1–2 kg (2.2–4.4 lb) in weight, surpassing related modern Australian wood duck (800 g (1.8 lb)).[475]

Pelicans, ibises and allies (Pelecaniformes)

The Early Pliocene Pelecanus schreiberi was larger than most extant pelicans. Pelecanus odessanus from the Late Miocene was probably the same size as P. schreiberi, its tarsometatarsus is 150 mm (5.9 in) long.[476]

Storks and allies (Ciconiiformes)

The largest known of Ciconiiformes was Leptoptilos robustus, standing 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) tall and weighing an estimated 16 kg (35 lb).[477][478]

Cranes (Gruiformes)

A huge true crane (Gruinae) from the late Miocene (Tortonian) of Germany was equal in size to the biggest extant cranes and resembled the long-beaked Siberian crane (Leucogeranus leucogeranus).[479]

Shorebirds (Charadriiformes)

Miomancalla howardi was the largest charadriiform of all time, weighing approximately 1.5 ft (0.46 m)(?) more than the great auk with a height of approximately 1 m (3.3 ft).[480]

Hesperornithines (Hesperornithes)

The largest known of the hesperornithines was Canadaga arctica at 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) long.[481]

New World vultures (Cathartiformes)

One of the heaviest flying bird ever was Argentavis from the family Teratornithidae. The immense bird had a wingspan estimated up to 5.09–6.5 m (16.7–21.3 ft)[452][453] and a weight up to 70 to 72 kg (154 to 159 lb).[482][452] Argentavis's humerus was only slightly shorter than an entire human arm.[483] Another huge teratorn was Aiolornis, it had a wingspan around 5 m (16 ft).[484] The Pleistocene Teratornis merriami reached 13.7 kg (30 lb) and 2.94–3.38 m (9.6–11.1 ft) in wingspan.[485] Even with lower estimates, it was larger than the observed California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) of nowadays.[485]

Seriemas and allies (Cariamiformes)

The largest known-ever Cariamiforme and largest phorusrhacid or "terror bird" (highly predatory, flightless birds of America) was Brontornis, which was about 175 cm (69 in) tall at the shoulder, could raise its head 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) above the ground and could have weighed as much as 400 kg (880 lb).[486] The immense phorusrhacid Kelenken stood 3 m (9.8 ft) tall[487][488] with a skull 716 mm (28.2 in) long (460 mm (18 in) of which was beak), had the largest head of any known bird.[487] South American Phorusrhacos stood nearly 2.4 to 2.7 meters (7 ft 10 in to 8 ft 10 in) tall, and probably weighed nearly 130 kilograms (290 lb), as much as a male ostrich.[489][490] The largest North American phorusrhacid is Titanis, which is about 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) tall,[491] as tall as a forest elephant.

Accipitriforms (Accipitriformes)

The largest known bird of prey ever was the enormous Haast's eagle (Hieraaetus moorei), with a wingspan of 2.6 to 3 m (8 ft 6 in to 9 ft 10 in), relatively short for their size.[492][493] Total length was probably up to 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) in female[494] and they weighed about 10 to 15 kg (22 to 33 lb).[495] Another giant extinct hawk was Titanohierax about 7.3 kg (16 lb) that lived in the Antilles and The Bahamas, where it was among the top predators.[496] An unnamed late Quaternary eagle from Hispaniola could be 15–30% larger than the modern golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos).[497] Some extinct species of Buteogallus surpassed their extant relatives in size. Buteogallus borrasi was about 33% larger than the modern great black hawk (B. urubitinga).[498] B. daggetti, also known as "walking eagle", was around 40% larger than the savanna hawk (B. meridionalis).[499] Eyles's harrier (Circus eylesi) from the Pleistocene-Holocene of New Zealand was more than twice heavier than the extant C. approximans.[500]

Moa (Dinornithiformes)

The tallest known bird was the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus), part of the moa family of New Zealand that went extinct about 500 years ago. It stood up to 3.7 m (12 ft) tall,[451] and weighed approximately half as much as a large elephant bird due to its comparatively slender frame.[450]

Tinamous (Tinamiformes)

MPLK-03, a tinamou specimen that existed during the Late Pleistocene in Argentina, possibly belongs to the modern genus Eudromia and surpacces extant E. elegans and E. formosa in size by 2.2-8% and 6-14%, respectively.[501]

Elephant birds (Aepyornithiformes)

The largest bird in the fossil record may be the extinct elephant birds (Vorombe, Aepyornis) of Madagascar, which were related to the ostrich. They exceeded 3 m (9.8 ft) in height and 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) in weight.[450]

Ostriches (Struthioniformes)

With 450 kg (990 lb) in body mass, Pachystruthio dmanisensis from the lower Pleistocene of Crimea was the largest bird ever recorded in Europe. Despite its giant size, it was a good runner.[502] A possible specimen of Pachystruthio from the lower Pleistocene of Hebei Province (China) was about 300 kg (660 lb) in weight, twice heavier than the common ostrich (Struthio camelus).[503] Remains of the massive asian ostrich (Struthio asiaticus) from the Pliocene[504] indicate a size 20% bigger than adult male of the extant Struthio camelus.[505]

Pigeons and doves (Columbiformes)

The largest pigeon relative known was the dodo (Raphus cucullatus), possibly exceeding 1 m (3.3 ft) in height and weighing as much as 28 kg (62 lb), although recent estimates have indicated that an average wild dodo weighed much less at approximately 10.2 kg (22 lb).[506][507]

Pheasants, turkeys, gamebirds and allies (Galliformes)

The largest known of the Galliformes was likely the giant malleefowl, which could reach 7 kg (15 lb) in weight.[508]

Songbirds (Passeriformes)

The largest known songbird is the extinct giant grosbeak (Chloridops regiskongi) at 280 mm (11 in) long.[citation needed]

Cormorants and allies (Suliformes)

- The largest known cormorant was the spectacled cormorant of the North Pacific (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus), which became extinct around 1850 and averaged around 6.4 kg (14 lb) and 1.15 m (3 ft 9 in).[509]

- The largest known darter was Giganhinga with estimated weight about 17.7 kg (39 lb),[510] earlier study even claims 25.7 kg (57 lb).[511]

- The largest known plotopterid, penguin-like flightless bird was Copepteryx titan that is known from 22 cm (8.7 in) long femur, almost twice as long as that of emperor penguin.[512]

Grebes (Podicipediformes)

The largest known grebe, the Atitlán grebe (Podylimbus gigas), reached a length of about 46–50 centimetres (18–20 in).[513]

Bony-toothed birds (Odontopterygiformes)

The largest known of the Odontopterygiformes— a group which has been variously allied with Procellariiformes, Pelecaniformes and Anseriformes and the largest flying birds of all time other than Argentavis were the huge Pelagornis, Cyphornis, Dasornis, Gigantornis and Osteodontornis.[citation needed] They had a wingspan of 5.5–6 m (18–20 ft) and stood about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) tall.[citation needed] Exact size estimates and judging which one was largest are not yet possible for these birds, as their bones were extremely thin-walled, light and fragile, and thus most are only known from very incomplete remains.[citation needed]

Woodpeckers and allies (Piciformes)

The largest known woodpecker is the possibly extinct imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) with a total length of about 56–60 cm (22–24 in).[514]

Parrots (Psittaciformes)

The largest known parrot is the extinct Heracles inexpectatus with a length of about 1 meter (3.3 feet).[515]

Penguins (Sphenisciformes)

The largest known penguin of all time was Palaeeudyptes klekowskii of Antarctica, its body length (tip of the bill to tip of the tail) is estimated about 2.02 m (6 ft 8 in) and body weight is estimated about 116.21 kg (256.2 lb).[516] Another large penguin is Anthropornis nordenskjoeldi of New Zealand and Antarctica. Its body length is estimated 1.99 m (6 ft 6 in) and was 97.8 kg (216 lb) in weight. There is also an estimate that one remain of Anthropornis can reach that body length of 2.05 m (6 ft 9 in) and 108 kg (238 lb) in weight.[517] Similar in size were the New Zealand giant penguin (Pachydyptes pondeorsus) with a height of 1.4 to 1.6 m (4 ft 7 in to 5 ft 3 in) and weighing possibly around 80 to 100 kg (180 to 220 lb) and over, and Icadyptes salasi at 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall.[518]

Owls (Strigiformes)

The largest known owl of all time was the Cuban Ornimegalonyx at 1,100 mm (43.3 in) tall probably exceeding 9 kg (20 lb).[519]

Amphibians (Amphibia)

The largest known amphibian of all time was the 9.1 m (30 ft) long temnospondyl Prionosuchus.[520]

Lissamphibians (Lissamphibia)

Frogs and toads (Anura)

The largest known frog ever was an as yet unnamed Eocene species that was about 58–59.1-centimetre-long (22.8–23.3 in).[521] The Late Cretaceous Beelzebufo grew to at least 23.2 cm (9.1 in) (snout-vent length), which is around the size of a modern African bullfrog.[522]

Salamanders, newts and allies (Urodela)

- Andrias matthewi was the largest lissamphibian ever known, with total length up to 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in).[523]

- Habrosaurus was the largest sirenid. It reached 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) long.[524]

Diadectomorphs (Diadectomorpha)

The largest known diacectid, herbivorous Diadectes, was a heavily built animal, up to 3 m (9.8 ft) long, with thick vertebrae and ribs.[525][526]

Anthracosauria

The largest known anthracosaur was Anthracosaurus, with skull about 40 cm (16 in) in length.[527]

Embolomeri

The longest member of this group was Eogyrinus attheyi, species sometimes placed under genus Pholiderpeton.[528] Its skull had length about 41 cm (16 in).[529]

Temnospondyls (Temnospondyli)

The largest known temnospondyl amphibian is Prionosuchus, which grew to lengths of 9 m (30 ft).[520] Another huge temnospondyl was Mastodonsaurus giganteus at 6 m (20 ft) long.[530] Unnamed species of temnospondyl from Lesotho is partial, but possible body length estimation is 7 m (23 ft).[531]

Fishes (Pisces)

Fishes are a paraphyletic group of non-tetrapod vertebrates.

Jawless fish (Agnatha)

Conodonts (Conodonta)

Iowagnathus grandis is estimated to have length over 50 cm (1.6 ft).[532]

Heterostracans (Heterostraci)

Some members of Psammosteidae such as Obruchevia and Tartuosteus are estimated to reached up to 2 m (6.6 ft).[533]

Thelodonts (Thelodonti)

Although known from partial materials, Thelodus parvidens (=T. macintoshi) is estimated to reached up to 1 m (3.3 ft).[534]

Cephalaspidomorphs (Cephalaspidomorphi)

A species of Parameteoraspis reached up to 1 m (3.3 ft).[535]

Spiny sharks (Acanthodii)

The largest of the now-extinct Acanthodii was Xylacanthus grandis, an ischnacanthiform based on a ~35 cm (14 in) long jaw bone. Based on the proportions of its relative Ischnacanthus, X. grandis had an estimated total length of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in).[536]

Placoderms (Placodermi)

The largest known placoderm was the giant predatory Dunkleosteus. The largest and most well known species was D. terrelli, which grew almost 9 m (29.5 ft) in length[537] and 4 t (4.4 short tons)[538] in weight. Its filter feeding relative, Titanichthys, may have rivaled it in size.[539] Titanichthys reached a length of 7 m (23 ft)[540][541] though in older paper it was estimated at 7.5 m (25 ft).[542]

Cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes)

Mackerel sharks (Lamniformes)

- Species in the extinct genus Otodus were huge. A giant shark, Otodus megalodon[543][544][545] is by far the biggest mackerel shark ever known.[546] Most estimates of megalodon's size extrapolate from teeth, with maximum length estimates up to 10–20.3 m (33–67 ft)[544][545][547] and average length estimates of 10.5 m (34 ft).[548][549] Due to fragmentary remains, there have been many contradictory size estimates for megalodon, as they can only be drawn from fossil teeth and vertebrae.[550]: 87 [551] Mature male megalodon may have had a body mass of 12.6 to 33.9 metric tons (13.9 to 37.4 short tons), and mature females may have been 27.4 to 59.4 metric tons (30.2 to 65.5 short tons), assuming that males could range in length from 10.5 to 14.3 m (34 to 47 ft) and females 13.3 to 17 m (44 to 56 ft).[552] Related to megalodon, Otodus angustidens and O. chubutensis reached the large sizes too. Each was estimated at 9.3 m (31 ft)[553] and 12.2 m (40 ft),[554] respectively.

- Other giant mackerel sharks were Pseudoscapanorhynchidae from the Cretaceous period. Cretodus had a size range of 9–11 m (30–36 ft) (for C. crassidens),[555] Leptostyrax reached lengths of 6.3–8.3 m (21–27 ft).[556]

- The Cenozoic Parotodus reached up to 7.6 m (25 ft) in length.[557]

- The heaviest thresher shark was likely Alopias grandis. It was similar in size or even larger than the extant great white shark and probably did not have an elongated dorsal tail, characteristic of modern relatives.[558]

Ground sharks (Carcharhiniformes)

The Cenozoic Hemipristis serra was considerably larger than its modern-day relatives and had much larger teeth. Its total length is estimated to be at 6 metres (20 ft) long.[559]

Hybodonts (Hybodontiformes)

One of the largest hybodontiforms was the Jurassic Asteracanthus with body length of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[560] Crassodus reifi is known from less materials, however it is estimated that reached over 3 m (9.8 ft).[561]

Skates and allies (Rajiformes)

The giant sclerorhynchid Onchopristis reached about 4.25 m (13.9 ft) in length.[562]

Eugeneodont (Eugeneodontida)

The largest known eugeneodont is an as-yet unnamed species of Helicoprion discovered in Idaho. The specimens suggest an animal that possibly exceeded 12 m (39 ft) in length.[563] Another fairly large eugeneodont is Parahelicoprion. Being more slimmer than Helicoprion, it reached nearly the same size,[563] possibly up to 12 m (39 ft) in length.[564] Both had the largest sizes among the animals of Paleozoic era.[565][564]

Lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii)

Coelacanths (Actinistia)

The largest coelacanth is Cretaceous Mawsonia gigas with estimated total length up to 5.3 m (17 ft). Jurassic Trachymetopon may have reached size close to that, about 5 m (16 ft).[566] An undetermined mawsoniid from the Maastrichtian deposits of Morocco probably reached 3.65–5.52 m (12.0–18.1 ft) in length.[567][566]

Lungfish (Dipnoi)

Cretaceous Ceratodus sp. from Western Interior is estimated to had a length around 4 m (13 ft).[568]

Stem-tetrapods (Tetrapodomorpha)

- Not only the largest known rhizodont, but also the largest lobe-finned fish was the 6–7 m (20–23 ft) long Rhizodus.[569] Another large rhizodonts were Strepsodus with estimated length around 3–5 m (9.8–16.4 ft) and Barameda estimated at 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft) in length.[570][571]

- Tristichopterid Hyneria reached length up to 4 m (13 ft).[572]

Ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii)

Pachycormiformes

The largest known ray-finned fish and largest bony fish of all time was the pachycormid, Leedsichthys problematicus, at around 16.5 m (54 ft) long.[573] Earlier estimates have had claims of larger individuals with lengths over 27 m (89 ft).[574][575]

Ichthyodectiformes

The largest known of ichthyodectiform fish was Xiphactinus, which measured up to 6.1 m (20 ft) long.[576] Ichthyodectes reached 3 m (9.8 ft) long, twice lesser than Xiphactinus.[577]

Bichirs (Polypteriformes)

The Late Cretaceous Bawitius was likely the largest bichir of all time. It reached up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length.[578]

Opahes, ribbonfishes, oarfishes and allies (Lampriformes)

Megalampris was likely the largest fossil opah. This fish was around 4 m (13 ft) in length when alive, which is twice the length of the largest living opah species, Lampris guttatus.[579]

Salmon and trout (Salmoniformes)

The largest salmon was Oncorhynchus rastrosus, varying in size from 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) and 177 kg (390 lb)[580] to 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) and 200 kg (440 lb).[581][580]

Pufferfishes, boxfishes, triggerfishes, ocean sunfishes and allies (Tetraodontiformes)

- Austromola angerhoferi had total body length about 3.2 m (10 ft), and total height 4 m (13 ft), comparable with largest ocean sunfish.[582][583]

- Some extinct species of Balistes like B. vegai and B. crassidens are estimated to have total length up to 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in).[584]

Lizardfishes (Aulopiformes)

The largest lizardfish was Stratodus which could reach length of 5 m (16 ft).[585]

Echinoderms (Echinodermata)

Crinozoa

Sea lilies (Cricoidea)

Longest stem of Seirocrinus subangularis reached over 26 m (85 ft).[586]

Asterozoa

Starfish (Asteroidea)

Helianthaster from Hunsrück Slate had radius about 25 cm (9.8 in).[587]

Graptolites (Graptolithina)

The longest known graptoloid graptolite is Stimulograptus halli at 1.45 m (4.8 ft). It found in Silurian deposits of the United Kingdom.[588]

Kinorhynchs (Kinorhyncha)

Cambrian kinorhynchs from Qingjiang biota, also known as "mud dragons", reached 4 cm (1.6 in) in length, much larger than extant relatives that grow only a few millimeters in length.[589][590]

Arthropods (Arthropoda)

Dinocaridida

Gilled lobopodians

Based on the findings of mouthparts, the Cambrian gilled lobopodian Omnidens amplus is estimated to have been 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[591] It is also known as the largest Cambrian animal known to exist.[591]

Radiodont (Radiodonta)

The largest known radiodont is Aegirocassis benmoulai, estimated to have been at least 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long.[592][593]

Chelicerata

Sea spiders (Pycnogonida)

The largest fossil sea spider is Palaeoisopus problematicus with legspan about 32 cm (13 in).[594]

Horseshoe crabs and allies (Xiphosura)

- Willwerathia reached 9 cm (3.5 in) in carapace width and was the largest species of basal ("synziphosurine") xiphosurans.[595][596] However, the Devonian Maldybulakia reached nearly 11.5 cm (4.5 in)[597] and was assigned to xiphosurans in 2013.[596]

- Horseshoe crab trackway icnofossil Kouphichnium lithographicum from Cerin in Ain indicates length of animal 77.4–85.1 cm (30.5–33.5 in).[598]

Chasmataspidids (Chasmataspidida)

The largest chasmataspidids were the Ordovician Hoplitaspis at 29 cm (11 in) in length and similar in size range Chasmataspis.[599]

Eurypterids (Eurypterida)